The history of Sigiriya, however, extends from prehistoric times to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The earliest evidence of human habitation is in the Aligala rock-shelter which lies to the east of the Sigiriya rock. This is a major prehistoric site of the mesolithic period, with an occupational sequence starting nearly five thousand years ago and extending up to early historic times. The historical period at Sigiriya begins about the third century B.C., with the establishment of a Buddhist monastic settlement on the rock-strewn western and northern slopes of the hill around the rock. As in other similar sites of this period, partially man¬made rock-shelters or 'caves', with deeply-incised protective grooves or drip¬ledges, were created in the bases of several large boulders. There are altogether 30 such shelters, many of them dated by the donatory inscriptions carved in the rock face near their drip-ledges to a period between the third century B.C., and the first century A.D. The inscriptions record the granting of these caves to the Buddhist monastic order to be used as residences.

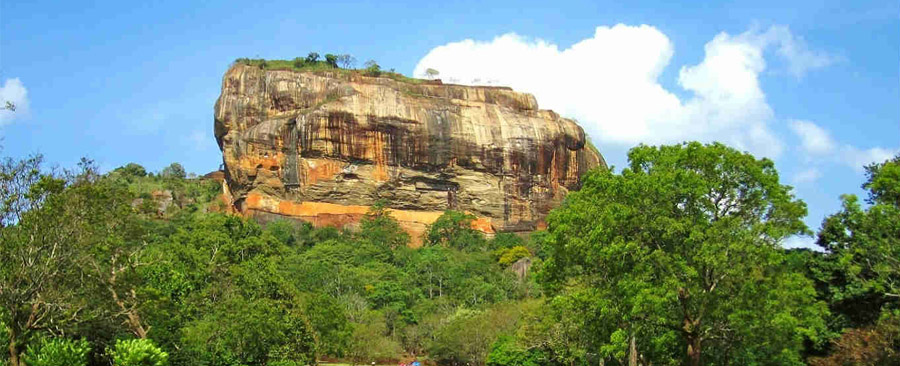

Sigiriya comes dramatically, if tragically, into the political history of Sri Lanka in the last quarter of the fifth century during the reign of King Dhatusena I (459-477 A.D.), who ruled from the ancient capital at Anuradhapura. A palace coup by Prince Kasyapa, the King's son by a non-royal consort, and Migara, the king's nephew and army commander, led ultimately to the seizure of the throne and the subsequent execution of Dhatusena. Kasyapa, much reviled for his patricide, established a new capital at Sigiriya, while the crown prince, his half-brother Moggallana, went into exile in India. Kasyapa 1 (477-495 A.D.) and his master-builders gave the site its present name, 'Simha-girl' or 'Lion-Mountain', and were responsible for most of the structures and the complex plan that we see today. This brief Kasyapan phase was the golden age of Sigiriya.

The post-Kasyapan phases, when Sigiriya was turned back into a Buddhist monastery, seem to have lasted until the thirteenth or fourteenth century. Sigiriya then disappears for a time from the history of Sri Lanka until, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it appears again as a distant outpost and military centre of the Kingdom of Kandy. In the mid¬nineteenth century antiquarians begin to take an interest in the site, followed some decades later by archaeologists, who have now been working there for nearly 100 years, since the 1890s. The Cultural Triangle project began its work at Sigiriya in 1982 and has focussed attention not only on the best-known and most striking aspects of Sigiriya: the royal complex of rock, palace, gardens and fortifications of the 'western precinct', but also on the entire city and its rural hinterland.

The most famous features of the Sigiriya complex are the fifth-century paintings found in a depression on the rock face more than 100 metres above ground level. Reached today by a modern spiral staircase, they are but fragmentary survivals of an immense backdrop of paintings that once extended in a wide band across the western face of the rock. The painted band seems to have extended to the north-eastern corner of the rock, covering thereby an area nearly 140 metres long and, at its widest, about 40 metres high. As John Still observed, 'The whole face of the hill appears to have been a gigantic picture Gallery ... the largest picture in the world perhaps' (Still 1907: I5).

The Mirror Wall dates from the fifth century and has been substantially preserved in its original form. Built up from the base of the rock itself with brick masonry, the wall has a highly polished plaster finish, from which it gets its ancient name, the Mirror Wall. The wall encloses a walk or Gallery paved with polished marble slabs. The famous Sigiriya paintings arc found in a depression high above this gallery. The polished inner surface of the mirror wall contains the Sigiriya Graffiti as described above.

One of the major foci of the Cultural Triangle excavations has been the Sigiriya gardens. Sigiriya provides us with a unique and relatively little known example of what is one of the oldest landscaped gardens in the world, whose skeletal layout and significant features are still in a fair state of preservation. Three distinct but interlinked forms are found here: water gardens, cave and boulder gardens, and stepped or terraced gardens encircling the rock. A combination of these three garden types is also seen in the palace gardens on the summit of the rock.

The water gardens arc, perhaps, the most extensive and intricate, and occupy the central section of the western precinct. 'Three principal gardens lie along the central cast-west axis. The largest of these, Garden 1, consists of a central island surrounded by water and linked to the main precinct by cardinally oriented causeways. The quartered or char bhag plan thus created, constitutes a well-known ancient garden form, of which the Sigiriya version is one of the oldest surviving examples. The entire garden is a walled enclosure with gateways placed at the head of each causeway. The largest of these gateways, to the west, has a triple entrance. The cavity left by the massive timber doorposts indicates that it was an elaborate gatehouse of timber and brick masonry with multiple, tiled roofs.